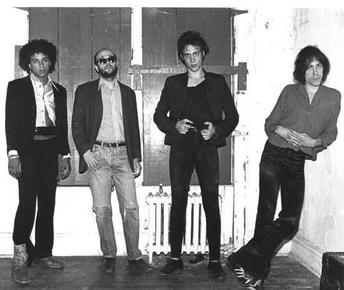

I was born in 1960 and so was 17 when Richard Hell and the Voidoids released ‘Blank Generation’. The title of this post is a play on the title of the song. It wasn’t a huge hit when it first came out and it hasn’t particularly stood the test of time, so I imagine you’d have to be about the same age as me to recognise my wordplay – and quite likely not even then. All generations have stuff that only they can relate to and the memory of which will die out when they do. I suspect Mr Hell’s oeuvre will fall into that category.

When you were born affects what you experience, and what you remember. This feeds into your attitudes and opinions. Brexit is a good example of how different age groups see things differently. Current affairs and politics first started to seep into my life when I was around 12 or 13 in the early seventies. Looking back I can now recognise that as a fairly remarkable time in the history of the UK, but while I was living in it I had nothing to compare it with and it seemed normal. One of the issues was Europe – and what was known at the time as the Common Market. This was rarely front page news. It didn’t involve bombs going off, strikes or power cuts and so didn’t seem especially important or interesting. Nonetheless a referendum was held on the subject. That this was a constitutional innovation in itself didn’t register with me.

I don’t remember being especially interested in the debate, and was just too young to vote so wasn’t put on the spot by a ballot paper. I think I would have voted against. All the grown ups seemed to be in favour so I was against. My parents were keen. My Normandy veteran grandfather was a great europhile and supporting joining the common market is the only political opinion I ever remember him expressing. It only occurred to me after the 2016 vote that he was probably thinking about avoiding another war.

And the war was something I was very interested in. I collected and glued together Airfix models and was particularly keen on the aircraft. I had the stereotypical badly painted Avro Lancaster hanging from my bedroom ceiling.

I’ve maintained that intense level of interest in WWII into and through my adult life. I can name a surprising number of generals from the Russian front. I recognise by sight most of the important fighters and bombers used in the conflict. I could easily outline the course of the whole war from memory. This doesn’t diminish my interest in finding out more about it. In fact, I am still slightly mystified why nobody has created a dedicated World War Two television channel. I don’t doubt that I and many others would watch it regularly.

This has, inevitably, affected my opinions about many other subjects. This is most true of my view of the European Union. The one thing I started to realise as I got beyond puberty was that the focus of my fascination was a huge catastrophe for mankind in general and for Europe in particular. The horrors of Nazism are so extreme that it is hard to comprehend how they came about even if you know a lot about it – and trust me I know my Nazis. Often by christian name.

So when I think about the EU the biggest thing that strikes me is that it is a force for peace. We never want to have 1939 again. And the EU more or less guarantees that fact. It doesn’t really matter what else it does well or badly. If it does that, then its existence is justified and our membership a necessity.

Unfortunately none of this helped me understand how I should vote in 2016. I never really thought through the consequences of leaving. I would have voted to remain even if it meant fishermen in the UK getting a poor deal or having to pay more for food. It didn’t really matter compared to the risk of another war. So I can’t blame leavers who were equally reckless about financial damage when they cast their ballot.

So now we have actually left I am totally shocked at just how important the EU has turned out to be to how we live our lives on a daily basis. The EU doesn’t only provide the peace it was set up for. The economic benefits are worth the admission price on their own. And the UK, perhaps more than any other member state, is really reliant on those economic benefits. I hadn’t grasped just how closely integrated we are with the economy of the continent and just how big a hit to our living standards being outside of it will be.

And it was something I gave hardly a thought to when I voted.

I now realise that me and people my age have grown up with a really distorted view of the world. We aren’t really equipped with an accurate view of our place in the world. Britain is not unimportant, and its economy is significant. But it is very dependent on its connections. We also don’t realise how competitive the world is.

One of the things that most struck me in the aftermath of the decision to leave was the rapid commissioning of direct ferry services between Ireland and the continent – especially the Rosslare to Zeebrugge one. It goes the full length of the English Channel. Britannia no longer rules the waves, it doesn’t even pick up local traffic any more. But if we make it hard to trade with us, surely we should expect to be sidelined. As it happens, I didn’t expect it.

I’ve come to the realisation that a combination of geography and history has meant that people living in the UK since the war have been playing life on the easy setting. We still had the afterglow from the empire. We didn’t have the opportunity to go out and make a fortune from other people’s countries, but enough fortunes had been made and were being spent to give us a cushion in terms of income. And we didn’t need to pay for defending the empire any more. The availability of labour from the Commonwealth made running businesses easier than it would otherwise have been. Joining the EU opened up markets at minimal cost.

Fighting the Second World War had cost the UK a great deal. The wartime generation had seen off facism, which required a lot of sacrifice. And setting up the welfare state shortly afterwards added to the bill. Which was another sacrifice to make the world better. But by the sixties economic growth and inflation had made this easier to cope with and taxes could start falling. Universal education opened opportunities. Education was no longer the privilege of the elite. Anyone could learn stuff. This made for a more productive workforce, and a less deferential one.

Thatcherism cashed in the savings.

Thatcher’s policy of selling things off was sold as a way of spreading the benefits of capitalism to the wider public. We’d become a ‘share holding democracy’. Large state enterprises were sold at a discount. There’s no doubt a lot to be said about the wisdom of this, but it did mean that the people who happened to be around at the time got a windfall. The shares were sold at a discount to the market price and so you could if you chose simply buy them when they were issued and pocket the profit the next day.

Privatisation also created quite a few opportunities for riches. Steven Fry notably pointed out that by setting up a production company he could sell his creativity to the BBC for more money than he would have got being employed by them directly. He wasn’t alone. Across rail, water, energy and latterly the post office many senior managers transitioned to company directors of large enterprises without the need for any actual risk – or even much in the way of enterprise.

The state sell-off that had the widest impact was the sale of council housing, once again at a substantial discount. This created millions of new homeowners, who then found that their cheaply bought asset was increasing in value. Everyone likes free stuff. The financial services industry even made it easy to extract the value of the property so the gains could actually be spent.

As if that wasn’t enough, the amount the state spent on things like health, education and defence was curtailed in favour of tax cuts. So all in all, the process was one of consumption today paid for by accumulated wealth from the past and leaving no inheritance for the future. The result has been that my generation has had a comfortable life. But we haven’t got much to point to in terms of collective achievements.

It’s one of the hardest things to accept really. We all like to think we have achieved what we have achieved in the face of tough odds, not that we had an easy ride. The spending spree has been unravelling for a while now. In some parts of the country the shortage of skilled and educated workers has combined with the lack of infrastructure to create areas of low economic activity. These areas are still not extensive, but are growing rather than shrinking. It used to be called the North-South divide – but the left behind bits now encompass bits of the Midlands and coastal resorts as well. So we are getting increasingly diverse misery.

So into all this came Brexit.

It took a while for me to even realise it was serious. I hadn’t thought much about the EU since the early eighties. When the Labour Party dropped its plan to leave that seemed to settle the question. I assumed that the Conservatives were always going to be in favour of something that was clearly good for business and frankly it didn’t seem to me that big a deal one way or the other. When the referendum was called I gave almost no thought which way I was going to vote. The basic idea of stopping war in Europe seemed positive, and I tend to think of myself as a European primarily. I didn’t worry about the business side of things. I assumed that if we left it would be in a way that wouldn’t harm trade. So although I voted to remain, it didn’t seem to be that crucial a decision. If we did vote out, we’d be back in fairly soon. It would be much like when France left NATO for a few years.

I didn’t get really wound up until about 2019, when it became clear that the plan was to totally tear up our relationship with Europe. This was obviously going to be enormously damaging to the UK’s prosperity, as is proving to be the case. I really wasn’t very quick on the uptake.

It’s been an education. But it’s a bitter lesson. Our grandparents fought off fascism. Our parents built the welfare state. All we’ve done is sell off the family furniture and blow the savings, then for an encore picked a fight with all our neighbours. It’s a pretty rubbish legacy for our children.