Following the assassination of Probus, the Praetorian prefect Carus was on hand and was well placed to succeed. He rapidly took over and he seemed to know what he was doing. He was about 60 with two sons and with none of the liberal inclinations of Probus. He did not trouble to get approval from the Senate. And from now on, the sham of senatorial approval of the emperor was dropped forever. Carus had an obscure origin. He appears to have been a senator but there is little evidence of him doing a great deal in that capacity. But he was definitely a soldier. He gave his two sons the title of Ceasar and sent one of them, Carinus, to Gaul to sort out a rebellion. He himself set out with Numerian, the other son on the long postponed punishment of Persia.

He was impatient to get going and marched to the border in the depths of winter. The Persians were, justifiably, worried. They sent ambassadors to the camp of the Romans to sue for peace. The elegantly dressed diplomats were escorted to the presence of Carus who was dressed like an ordinary soldier and eating a standard issue meal of stale bacon and hard peas. Only a coarse wool garment of purple indicated his rank. The interview did not go well. Carus removed his cap to reveal his bald head and said that it was either abject surrender, or he would render Persia as bare of trees as his scalp was bare of hair. The officials retreated in terror.

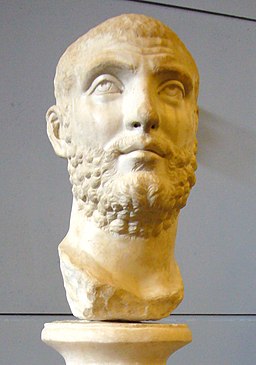

|

| Carus – note the bald head (Thanks to Wikipedia for the image) |

Carus was as good as his word and invaded Persia spreading havoc. The Persian capital surrendered to him, apparently without a fight. The timing of the attack had been perfect. Indeed the haste of Carus to prosecute the invasion may well have been due to intelligence that the moment to strike had come. The Persians had been troubled with civil war before the invasion and the blow struck by Rome looked likely to prove fatal. The Persian empire was about to be ended by the renewed strength of Rome.

But the Persians had the most bizarre of escapes. Carus fell ill on campaign, and with each day got steadily worse. One day he died. He happened to die during a severe thunderstorm. And shortly after his death, his tent caught fire. The conjunction of the storm and the fire, led to a rumour going around that he had been struck by lightning. This detail may not immediately seem significant to modern ears, but it made all the difference in the ancient world. Thunder was the specific means of communication of the great god Jupiter. By striking down Carus with a thunderbolt the King of the Gods was indicating divine displeasure with the invasion of Persia.

Being on hand and clearly being the legitimate successor, the son of Carus was immediately proclaimed as the new emperor. Numerian’s authority as the new emperor was not in question, but a higher authority still was instructing the army to go home, or so thought the superstitious rank and file soldiers. Against the power of opinion even an acknowledged sovereign is impotent. The men wanted to go home and nothing could stop them. Numerian’s view of the matter is not recorded but was in any case irrelevant. The Persians had had a lucky escape.

Numerian and his brother Carinus had only had 16 months to get used to the idea of being emperors. Carinus in particular did not really seem to have the ideal personality for a sovereign. It is not a good sign when he put to death old school friends whose only crime was to have known him before his unexpected elevation. He also abused his new found status as a highly eligible bachelor by marrying and divorcing 9 women in a few months, leaving most of them pregnant. Quite why he bothered with the legal formalities isn’t at all obvious given that his position gave him plenty of opportunities to enjoy himself in all sorts of ways, which he fully took advantage of.

Numerian on the other hand was a poet and an orator. He had established a literary reputation before he was taken on the expedition to Persia by his father. In a less violent age he might have made an appealling prince, but he was not up to the rigours of the camp. He soon fell ill – some kind of eye infection – and delegated the authority for day to day orders to his Praetorian Prefect Arrius Aper – who was also his father in law.

As the army marched home from the aborted Persian invasion, it was controlled from the imperial tent via written instructions that were soon being written on behalf of Numerian by his prefect. The actual emperor ceased to be visible at all. After a while rumours started to circulate that he had in fact died. Eventually and inevitably, some soldiers forced their way into the tent to discover the truth. Numerian was indeed dead.

The deception was Aper’s big mistake. It immediately cast him under suspicion and given the dramatic way the truth had come out he was instantly put in chains as the murderer of his master. Although he was no doubt innocent, you have to wonder what plan he had for getting out of the tricky situation he had created for himself. I hope he wasn’t considering ventriloquism.

An assembly of the whole army convened in Chalcedon to decide what was to be done. The leader that emerged from this was the chief of the body guard, Diocletian. But his previous job title did give him a bit of an issue. The body he had been charged with guarding had manifestly not been guarded all that well if Aper was guilty. On top of that, it looked very much like Diocletian was going to turn out to be the big beneficiary of the death of the person he was charged to protect.

Diocletian overcame this in dramatic form. His first act on being selected was to publicly declare his innocence calling the undying Sun in evidence as his witness. The next act was to personally kill Aper in front of the whole army. This gruesome bit of showmanship won the day and won him the loyalty of the legions. It also got rid of a man who might well have had an interesting story to tell about Diocletian’s role in the events, but we’ll never know.

What we do know is that there was still a considerable obstacle to Diocletian’s imperial ambitions in the form of Numerian’s brother Carinus. He was still inconveniently alive and in control of the legions in Gaul, legions which were more numerous and generally of a higher standard than the Eastern legions commanded by Diocletian. They also had the advantage that they hadn’t just been marched back from a distant campaign on foreign soil.

Carinus for all his faults had some good cards in his hand. He was very much the legitimate successor of his father. And he also had some public support. He had achieved this by a contemptuous attitude towards the senators, who he had publically announced his intention of depriving of their property. Bashing the rich always went down well with the plebians. The other way to cheer up the masses was by providing entertainment, and the circuses laid on by Carinus were probably the greatest shows ever laid on in Rome.

The comments about the games of Carinus are all glowing in their praise, but unfortunately we don’t have a specific review that tells us what they comprised of. We do know that some of the displays that Carinus managed to top were themselves pretty spectacular. We hear about trees being uprooted and planted in the Colosseum to form forests that were populated with wild beasts. The spectacle was to see them hunted and killed. The animals were brought from great distances, possibly as far as the island of Madagascar.

http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html), CC-BY-SA-3.0 (www.creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/) or CC-BY-SA-2.5-2.0-1.0 (www.creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.5-2.0-1.0)], via Wikimedia Commons”> |

| Carinus – Lavish games but lurid private life (thanks to Wikipedia for the image) |

What with Hollywood and television, we have become a bit jaded about entertainment. But looking from the vantage point of pre-Industrial Britain these games must have seemed astonishing, and there had been almost nothing remotely like them in the centuries since. Enlightenment values come to the fore when Gibbon laments that the Romans were not that interested in Natural History so didn’t bother to diligently record these animals before killing them. But on the whole, he is impressed both by the spectacle itself and the huge resources devoted to putting on a good show.

A huge awning could be spread across to shade the spectators – the ropes being handled with skill by the sailors from the Roman navy. The design allowed the arena to be flooded with water so that sea battles could be put on.

|

| The Colosseum was the last word in entertainment (Thanks to Wikipedia for the image) |

But his lavish games did not win over everybody. Carinus marched against Diocletian with a much greater army and met him in battle at Margus in modern day Serbia. He would have beaten Diocletian had he not been killed by one of his officers – the story being that Carinus had seduced his wife.

Although, as we have seen, during the previous couple of reigns Rome was definitely back up and fighting again the battle of Margus and the acsension of Diocletian is considered to be the end of the crisis by many. It was certainly a turning point as Diocletian was to make far ranging changes to the way the empire was organised as we will see in the next chapter.